Today, I gave a webinar presentation with Ken Phelps, President of Camargo Pharmaceutical Services, on the interaction of patents and exclusivity of drugs approved by the FDA under section 505(b)(2). Ken is an expert at 505(b)(2) filings so my job (covering patent issues) was pretty easy.

Ken notes that large pharma and small start-ups alike are keenly interested in these filings with no signs of letting up. It’s not hard to see why. Section section 505(b)(2) drug applications find a unique (although often neglected) place between innovative drug NDAs and and the generic ANDAs.

Section 505 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act describes three basic types of new drug applications:

- an application that contains full investigations of safety and effectiveness (section 505(b)(1));

- an application that contains full investigations of safety and effectiveness but where at least some of the information required for approval comes from studies not conducted by or for the applicant and for which the applicant has not obtained a right of reference (section 505(b)(2)); and

- an application that contains information to show that the proposed product is identical in active ingredient, dosage form, strength, route of administration, labeling, quality, performance characteristics, and intended use, among other things, to a previously approved product (section 505(j)).

An important benefit of 505(b)(2) applications compared to Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) is the ability to earn market exclusivity. Like ANDAs, 505(b)(2) submissions must include all relevant patents and patent certifications and are subject to the same Paragraph IV challenges and litigation, including a 30-month stay. However, 180-day exclusivity is not granted.

So, what type of information can an applicant rely on?

1. Published literature (a literature-based 505(b)(2)). If the applicant has not obtained a right of reference to the raw data underlying the published study or studies, the application is a 505(b)(2) application; if the applicant obtains a right of reference to the raw data, the application may be a full NDA (i.e., one submitted under section 505(b)(1)).

2. The Agency’s finding of safety and effectiveness for an approved drug to the extent such reliance would be permitted under the generic drug approval provisions at section 505(j). This approach is intended to encourage innovation in drug development without requiring duplicative studies to demonstrate what is already known about a drug while protecting the patent and exclusivity rights for the approved drug.

What kind of application can be submitted as a 505(b)(2) application? The applications are for either (a) new chemical entity (NCE)/new molecular entity (NME) or (b) changes to previously approved drugs — changes of the type described immediately below may not require review of information other than BA or BE studies or data from limited confirmatory testing:

- Dosage form

- Strength

- Route of administration

- Substitution of an active ingredient in a combination product.

- Formulation

- Dosing regimen

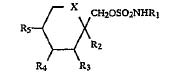

- Active ingredient, e.g., a different salt, ester, complex, chelate, clathrate, racemate, or enantiomer of an active ingredient in a listed drug containing the same active moiety.

- New molecular entity, often a prodrug of an approved drug or the active metabolite of an approved drug

- Combination product

- Indication

- Rx/OTC switch

- OTC monograph

- Naturally derived or recombinant active ingredient

- Bioinequivalence, where absorption is different from the 505(j) standards

You cannot submit an application that is a duplicate of a listed drug and eligible for approval under section 505(j) or submit an application where the only difference is the extent to which the active ingredient(s) is absorbed or otherwise made available to the site of action is less than the listed drug.

Why is all this trouble worth it? In a word: Exclusivity. A 505(b)(2) application may obtain 3 years of Waxman-Hatch exclusivity if one or more of the clinical investigations, other than BA/BE studies, was essential to approval of the application and was conducted or sponsored by the applicant. An applicant can get 5 years of exclusivity if it is for a new chemical entity. A 505(b)(2) application may also be eligible for orphan drug exclusivity or pediatric exclusivity.

Approval or filing of a 505(b)(2) application, like a 505(j) application, may be delayed because of patent and exclusivity rights that apply to the listed drug. This is the case even if the application also includes clinical investigations supporting approval of the application.

The 505(b)(2) application requires applicant to file patent certifications with application and serve notice on NDA holder and patent owner. This patent information will be published in the Orange Book when the application is approved. The types of filings include:

- Paragraph (I): no patent was listed in Orange Book

- Paragraph (II): listed patent has expired

- Paragraph (III): listed patent will expire before requestedapproval

- Paragraph (IV): listed patent is invalid or will not be infringed

The great thing about this is, if approved, is that the applicant will enjoy complete exclusivity. If the approval is for a new chemical entity (NCE), the exclusivity prohibits a generic manufacturer from submitting an ANDA for 5 years from date of NDA approval. Although, if an ANDA includes a paragraph IV certification, an ANDA can be filed after 4 years, but any 30-month stay is extended by up to 1 year (to expire 7-1/2 years after NDA approval).

An application for new clinical indications for approved products receive three years of exlusivity. This exclusivity prohibits FDA approval (but not submission) of an ANDA for 3 years after NDA/sNDA approval. Therefore, ANDA approval can come exactly 3 years later.

The period of time of exclusive marketing rights is granted by FDA at the time of approval and cannot be challenged or voided. The time runs from the date of approval, except for pediatric exclusivity, which attaches to an existing exclusivity or patent period.

All this and patent protection may apply also. What’s not to love?

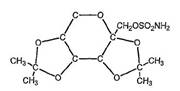

Ortho-McNeil kept it’s exclusivity on topiramate after a district court blocked Mylan Labs from infringing Ortho-McNeil’s

Ortho-McNeil kept it’s exclusivity on topiramate after a district court blocked Mylan Labs from infringing Ortho-McNeil’s