Conducting an IP audit is a way for a firm to assess the nature and value of its intellectual property assets. Such assessments may be critical and more commonplace in certain industries, such as IT and pharmaceuticals. However, in the wake of legislative changes and the current economic downturn, the potential value in conducting an IP audit may have become clearer in other industries as well.

Generally speaking, IP audits are either externally or internally driven. Externally driven IP audits are performed in response to triggers such as infringement litigation, bankruptcies, funding transactions, or transactions involving the sale of the business or certain assets. Under this circumstance, IP audits are often performed under time constraints and are, by their nature, reactive.

Internally driven IP audits, on the other hand, are initiated as a pro-active business practice by the holder of the IP. Internally driven IP audits can be used to identify:

- New revenue streams related to proprietary products and licensing;

- New sources of capital and funding;

- Strategic positioning/repositioning opportunities;

- Business risks and opportunities related to IP such as patent, copyright, or trademark applications that should be filed, or securing certain IP rights from employees;

- Business process changes in R&D, Engineering, HR, or other areas; and

- Financial reporting disclosure items related to IP.

However, in the wake of the credit meltdown it may be hard to justify a “spend money to make money” philosophy. How does a firm measure the potential value of internally driven IP audits in relation to a tougher economy?

To find out, I spoke with Glenn Perdue, an IP valuation expert. Perdue, who leads Kraft Analytics, LLC, a valuation and litigation support consulting firm in Nashville, Tennessee, has more than 20 years of experience in business strategy, technology strategy, capital formation, valuation and litigation support.

Is performing an IP audit a good move in today’s business climate?

In any business climate, it makes sense to identify and understand those assets that allow a company to create economic value for customers and owners. In the industrial age, value-enabling assets were largely physical in nature. Today, value-enabling assets are more intangible. It’s a generally accepted belief that the majority of public company market value is not value identified on a company’s balance sheet. Instead, most value is attributed to intangibles assets – often intellectual property – that may not appear on the balance sheet at all. Therefore, companies that rely on IP to create economic value should catalog and understand these intangible assets so that their value can be better managed and optimized. An IP audit is often a good starting point in this process. However, an IP audit is one component of a more comprehensive IP management approach that may include the following:

- IP Audit – The assessment component, which informs management as to the nature and value of their IP assets at a certain point in time.

- IP Planning and Policy Development – Based upon information obtained through the IP audit, legal counsel, and business/industry research, management develops IP plans and policies in an informed manner.

- Execution – After developing plans and policies, managers begin executing the plan through the implementation of business processes, licensing, enforcement, and other activities identified to optimize IP-related value creation.

- Analysis and Reporting – This final step allows management to assess results and refine the process. In addition to internal reporting, the IP management process may also yield information needed for disclosure in external financial reporting.

What advice would you offer an attorney who was presenting the idea of conducting an IP audit to his client?

Making the case for conducting an IP audit is situational. Reasons might include:

- A prospective business purchase or sale that involves IP assets

- IP sale or licensing transactions

- Equity transactions in which investors, such as VCs, consider IP assets to be a critical component of the deal

- Debt and securitization transactions that rely upon IP as the underlying collateral

- Bankruptcy and restructuring

- Post-transaction accounting requirements (e.g. FAS 141)

- Management insight and planning as related to marketing, finance, risk assessment, and business strategy

- Legal and regulatory compliance

Given this broad range of motivations, an attorney’s recommendation to conduct an IP audit may be event-specific. In the case of transactions involving IP, the due diligence process is similar to an audit in many ways. If the audit is required, convincing the client may not be an issue. However, if the audit is being suggested for planning or compliance purposes, risk mitigation or profit optimization motives should be articulated to make the business case.

What is the danger of not understanding one’s IP holdings?

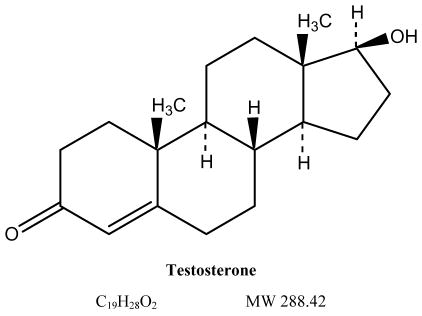

IP value is, first and foremost, contextual. The value of IP in the hands of one enterprise may be different than the value of the same IP in the hands of another enterprise. Access to the various means of exploiting IP assets is an important factor. Consider a drug patent held by a university. The university may hold the rights to an important piece of IP but lack the means of producing and marketing a major pharmaceutical product that embodies that patent and fully exploits its economic value. Since universities are not in the business of making products, they choose to license such inventions. Thus, the valuation issue faced by a university relates more to up-front, milestone, and royalty payments for the use of the IP by others. However, a pharmaceutical company that holds the same patent faces a broader decision as to whether it should (i) make and market the product itself, (ii) out-license the patent to another company that might be better-suited to optimizing the patent’s value, or (iii) use the patent in a more defensive manner. In this case, the pharmaceutical company might consider a valuation analysis as a basis for making this determination.

Tell me about the relation between IP audits and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act.

A broad view of Sarbanes-Oxley is that it requires corporate managers and directors to be better stewards of company assets – including IP assets – while providing greater transparency and accountability with respect to financial reporting. Given that IP assets are a predominant basis for value creation, particularly in science and technology-based companies, the duty of care imposed by Sarbanes-Oxley is considered applicable to IP assets by many. In light of this – and the fact that the value of these assets are typically not reflected in GAAP-based financial statements – many believe that IP assets, their economic value, and related risks must be accounted for elsewhere and disclosed if material. Thus, companies with material IP assets may be advised by counsel to conduct regular IP audits and valuations to maintain compliance with Sarbanes-Oxley.

Can you describe the need for IP audits in the non-profit sector?

I serve on several non-profit boards, including a research foundation board that performs the technology transfer function for a major university. I’ve witnessed first-hand how large non-profits are increasingly aware of accountability and transparency in their governance and financial reporting functions. I’ve also seen how this issue has affected non-profit hospitals. In the case of universities and private research institutions that generate IP, they may not be accountable to shareholders but they are certainly accountable to trustees, boards of directors, donors, and other stakeholders that place trust in them to be good stewards of the institution’s assets, in this case IP assets. Therefore, looking at it through this lens, such institutions may not be public companies and subject to Sarbanes-Oxley directly, but they may certainly be held to a similar standard of care and thus must be diligent in protecting and optimizing the value of their IP while also being mindful of the broader mission of their institution.

Sarbanes-Oxley regulates public companies. What about closely owned companies? Do you see much activity among them in your valuation practice?

Many lawyers I’ve spoken to about this issue contend that small growth companies considering an IPO or sale to a larger public company must move towards Sarbanes-Oxley compliance early on. However, even if an IPO or M&A transaction is not on the horizon, some attorneys suggest that the presence of outside investors in a private company can indirectly expose a company to Sarbanes–Oxley, which may be invoked as the basis for a standard of care that is owed the investors.

Is it wise for attorneys to suggest that experts be brought in to determine possible new product development, potential competitor infringement, etc.? If so, why?

In my work as an expert in IP-related litigation, I’m brought in by attorneys regularly to assist in cases. My experience with the attorneys I’ve worked with has been that they have a good sense of when and why outside experts need to be engaged. One of the primary factors to consider in this determination is the existence of internal expertise at the client company. The need for outside experts may be due to a lack of requisite expertise within the client company and/or the need to hire an outsider for purposes of objectivity. In the case of litigation or auditing, the objectivity of an outside expert is generally desired.

Today’s post is by Guest Barista Dawn Corrigan, who writes for IMS ExpertServicesâ„¢ – the premier expert witness delivery firm. This article was originally published in ipFrontline and subsequently appeared in BullsEye, the newsletter of IMS ExpertServices.

Indiana University’s Kelley School of Business last year started an online graduate level program, the Executive Certificate in the Business of Life Sciences (ECBLS). George Telthorst, who helps run the program and is the Director of Business Development at the School’s Center for the Business of Life Sciences, wants us to help “spread the word” about it.

Indiana University’s Kelley School of Business last year started an online graduate level program, the Executive Certificate in the Business of Life Sciences (ECBLS). George Telthorst, who helps run the program and is the Director of Business Development at the School’s Center for the Business of Life Sciences, wants us to help “spread the word” about it. Lawline.com

Lawline.com The

The  An English version of the current

An English version of the current  The

The