In In re Kubin (08-1184), the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit held that the US Patent and Trademark Office’s Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences was correct to hold claims as unpatentably obvious when applicants use “conventional techniques” to make an invention. This is bad news not just for biotech but for all arts.

In this case, the Board had rejected the claims of U.S. Patent Application Serial No. 09/667,859 as obvious under 35 U.S.C. § 103(a) and invalid under 35 U.S.C. § 112 ¶ 1 for lack of written description (Ex parte Kubin).

The application claims the isolation and sequencing of a human gene that encodes a particular domain of a protein, known as the Natural Killer Cell Activation Inducing Ligand (NAIL). Natural Killer cells express a number of surface molecules which, when stimulated, can activate cytotoxic mechanisms. NAIL is a specific receptor protein on the cell surface that plays a role in activating the NK cells.

The specification of the claimed invention recites an amino acid sequence of a NAIL polypeptide. The invention further isolates and sequences a polynucleotide that encodes a NAIL polypeptide. Moreover, the inventors allege discovery of a binding relationship between NAIL and a protein known as CD48, which causes an increase in cell cytotoxicity and in production of interferon.

Representative claim 73 is for the DNA that encodes the CD48-binding region of NAIL proteins:

73. An isolated nucleic acid molecule comprising a polynucleotide encoding a polypeptide at least 80% identical to amino acids 22-221 of SEQ ID NO:2, wherein the polypeptide binds CD48.

The applicants’ specification discloses nucleotide sequences for two polynucleotides: SEQ ID NO: 1 recites the specific coding sequence of NAIL, whereas SEQ ID NO: 3 recites the full NAIL gene, including upstream and downstream non-coding sequences. The specification also contemplates variants of NAIL that retain the same binding properties.

In rejecting the claims as invalid, the Board concluded that appellants were not entitled to their genus claim of DNA molecules encoding proteins 80% identical to SEQ ID NO:2:

Without a correlation between structure and function, the claim does little more than define the claimed invention by function. That is not sufficient to satisfy the written description requirement.

Regarding obviousness, the Board rejected the claims over the combined teachings of U.S. Patent No. 5,688,690 (Valiante) and Sambrook et al., Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual.

Valiante discloses a receptor protein p38, which is present on virtually all human NK cells and can serve as an activation marker for cytotoxic NK cells. Valiante also discloses and claims a monoclonal antibody specific for p38 called mAB C1.7. The Board found that Valiante’s p38 protein is the same protein as NAIL.

The court said that Valiante teaches that “[t]he DNA and protein sequences for the receptor p38 may be obtained by resort to conventional methodologies known to one of skill in the art.” Additionally, the DNA sequence encoding the receptor can be obtained by the “panning” technique of screening a human NK cell library by eukaryotic expression cloning, of which several are known.

With regard to the amino acid sequence referred to as SEQ ID NO:2, the court agree with the Board that:

Because of NAIL’s important role in the human immune response, the Board further found that “one of ordinary skill in the art would have recognized the value of isolating NAIL cDNA, and would have been motivated to apply conventional methodologies, such as those disclosed in Sambrook and utilized in Valiante, to do so.”

Based on this, the Board turned to the Supreme Court’s decision in KSR and concluded that claim was “the product not of innovation but of ordinary skill and common sense,’ leading us to conclude NAIL cDNA is not patentable as it would have been obvious to isolate it.”

Seeing that the Board concluded that the method of isolating NAIL DNA was essentially the same as the methodologies and teachings of Valiante and Sambrook, the Federal Circuit really didn’t care about any similarities or differences in methods of deriving the NAIL DNA since the claim in question was for a gene sequence:

[T]his court determines that the Board had substantial evidence to conclude that appellants used conventional techniques, as taught in Valiante and Sambrook, to isolate a gene sequence for NAIL.

Thus, Kubin and Goodwin cannot represent to the public that their claimed gene sequence can be derived and isolated by “standard biochemical methods” discussed in a well-known manual on cloning techniques, while at the same time discounting the relevance of that very manual to the obviousness of their claims. For this reason as well, substantial evidence supports the Board’s factual finding that “[a]ppellants employed conventional methods, ‘such as those outlined in Sambrook,’ to isolate a cDNA encoding NAIL and determine the cDNA’s full nucleotide sequence (SEQ NOS: 1 & 3).”

Because this court sustains, under substantial evidence review, the Board’s finding that Valiante’s p38 is the same protein as appellant’s NAIL, Valiante’s teaching to obtain cDNA encoding p38 also necessarily teaches one to obtain cDNA of NAIL that exhibits the CD48 binding property.

The court also looked at the assessment of obviousness in the context of classical biotechnological inventions, specifically In re Deuel. In Deuel, the Federal Circuit reversed the Board’s conclusion that a prior art reference teaching a method of gene cloning, together with a reference disclosing a partial amino acid sequence of a protein, rendered DNA molecules encoding the protein obvious. The court also stated that “obvious to try” is not the test for obviousness.

The Federal Circuit then noted that the Supreme Court cast doubt on the viability of Deuel to the extent the Federal Circuit rejected an “obvious to try” test in KSR:

Under KSR, it’s now apparent “obvious to try” may be an appropriate test in more situations than we previously contemplated.

So, when is an invention that was obvious to try nevertheless nonobvious? To differentiate between proper and improper applications of “obvious to try,” this court outlined two classes of situations where “obvious to try” is erroneously equated with obviousness under § 103:

In the first class of cases, what would have been “obvious to try” would have been to vary all parameters or try each of numerous possible choices until one possibly arrived at a successful result, where the prior art gave either no indication of which parameters were critical or no direction as to which of many possible choices is likely to be successful (“where a defendant merely throws metaphorical darts at a board filled with combinatorial prior art possibilities”).

The second class of impermissible “obvious to try” situations occurs where what was “obvious to try” was to explore a new technology or general approach that seemed to be a promising field of experimentation, where the prior art gave only general guidance as to the particular form of the claimed invention or how to achieve it (“the improvement is more than the predictable use of prior art elements according to their established functions”).

The court then applied this to the current case:

The record shows that the prior art teaches a protein of interest, a motivation to isolate the gene coding for that protein, and illustrative instructions to use a monoclonal antibody specific to the protein for cloning this gene. Therefore, the claimed invention is “the product not of innovation but of ordinary skill and common sense.” KSR, 550 U.S. at 421. Or stated in the familiar terms of this court’s longstanding case law, the record shows that a skilled artisan would have had a resoundingly “reasonable expectation of success” in deriving the claimed invention in light of the teachings of the prior art. See O’Farrell, 853 F.2d at 904.

This court also declines to cabin KSR to the “predictable arts” (as opposed to the “unpredictable art” of biotechnology). In fact, this record shows that one of skill in this advanced art would find these claimed “results” profoundly “predictable.”

In light of the concrete, specific teachings of Sambrook and Valiante, artisans in this field, as found by the Board in its expertise, had every motivation to seek and every reasonable expectation of success in achieving the sequence of the claimed invention. In that sense, the claimed invention was reasonably expected in light of the prior art and “obvious to try.”

What is amazing about this decision is that complex discoveries — biotechnology or not — are almost always made through a complex and lengthy process using well-established and validated research methods.

PatentlyBIOtech points out the obvious problem in this case:

Would the Patent Office rather that Kubin hadn’t even tried? What about further discoveries that build upon Kubin’s gene? Are those also unpatentable if they are made with routine research tools and methods? What about a medicine that might one day be developed based on Kubin’s discovery? Is that also just the result of routine experimentation, undeserving of a patent?

While In Re Kubin seems like a case where hindsight will be used to club every biotech patent, Patent Docs felt that this is not the end of biotech patents:

Another reason the sky will not be falling on biotechnology patenting arises from the time in the history of biotechnology in which the decision was handed down. Many (if not most) of the “known” genes in the art have been cloned and patented (or not) over the past 30 years of gene patenting, and many of these patents have expired or are nearing the ends of their terms. … Turning to the present day, many (if not most) of the genes patented or that have been attempted to be patented were not known prior to their discovery (usually through homology comparisons) as a result of the Human Genome Project (HGP). A fundamental pillar of the Court’s decision in Kubin was that p38 was known; that will not be the case for most of the genes identified since the late 1990’s.

This leaves a class of genes and gene patents “in the middle” — granted since (and perhaps because of) the Court’s decision in Deuel but prior to identification during the HGP effort. Some of these, no doubt, have been made more open to an obviousness challenge since the Court’s decision in this case. However, many (if not most) of these genes will be lacking some if not several of the factual underpinnings of the Kubin decision: the existence of the protein encoded therein was not known, or there was not a commercially-available monoclonal antibody specific for the protein, or expression cloning was ineffective or unpredictable for that gene, or there was no express description in the art on how to isolate the gene, or there did not exist a cell or tissue source reliably expressing the protein.

The only thing that’s certain is that the Patent Office will begin hammering biotech patents on obviousness more than ever — starting immediately.

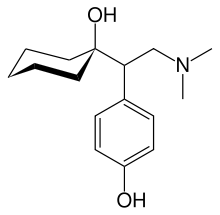

Wyeth markets racemic ODMV succinate in the U.S. under the brand name Pristiq® for the treatment of major depressive disorder in adults. Sepracor, if it wins the interference, could end up owning the patent rights that would then be infringed by Wyeth’s sale of Pristiq.

Wyeth markets racemic ODMV succinate in the U.S. under the brand name Pristiq® for the treatment of major depressive disorder in adults. Sepracor, if it wins the interference, could end up owning the patent rights that would then be infringed by Wyeth’s sale of Pristiq.