Abbott is the exclusive licensee of a patent for crystalline cefdinir, which it sells under the trade name Omnicef. Unfortunately, it hasn’t been able to catch a break.

In dueling district court cases, the Eastern District of Virginia granted summary judgment of noninfringement for Lupin Pharma and the Illinois District Court denied a preliminary injunction to Abbott Laboratories against Sandoz, based on the claim construction from the Eastern District of Virginia over U.S. Patent No. 4,935,507.

Abbott’s appeal found an unreceptive audience in the Federal Circuit who held that the claims were correctly construed and there was no infringement. Abbott v. Sandoz (07-1400/1446).

In Virginia, Lupin sought a declaratory judgment of noninfringement against Abbott Laboratories and Astellas Pharma, owner of the ’507 patent. The FDA had approved Lupin’s Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) to market a generic version of Omnicef. Lupin’s generic product contains almost exclusively the Crystal B form of crystalline cefdinir (cefdinir monohydrate), whereas Abbott’s Omnicef product contains the Crystal A form of crystalline cefdinir (cefdinir anhydrate). Further, Lupin makes its products with processes other than those claimed in the ’507 patent.

So, Lupin brought the Virginia action to settled the issue that its product would not infringe a valid patent. Abbott counterclaimed for infringement. The Eastern District of Virginia construed the claims and granted-in-part Lupin’s motion for summary judgment of noninfringement,

In the Illinois action, Abbott sued Sandoz (and Sandoz GmbH, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Ranbaxy Laboratories, Par Pharmaceutical) for infringement after they wanted to market generic versions of Omnicef. After disputing the meaning of terms such as “Crystal A,” “peaks,” and “about,” and seeking construction of “powder X-ray diffraction pattern,” Abbott appealed.

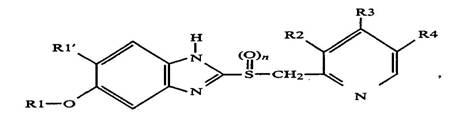

The ’507 patent claims crystalline cefdinir, using its chemical name crystalline 7-[2-(2-aminothiazol-4-yl)-2-hydroxyiminoacetamido]-3-vinyl-3-cephem.-4-carboxylic acid (syn isomer), and defining its unique characteristics with powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) angle peaks as a way to claim the structure and characteristics of the unique crystalline form.

The ’507 patent claims priority to Japanese Patent Application No. 62-206199, which claimed two crystalline forms of cefdinir, “Crystal A” and “Crystal B.” Despite using the JP ’199 application for priority, the ’507 patent’s specification jettisoned the Crystal B disclosure and used broader claims. Because the JP ’199 applications defines Crystal A and Crystal B physiochemically rather than structurally, the forms actually represent subgenuses of crystalline cefdinir.

In looking at the claim construction, the court said it must take care not to import limitations into the claims from the specification when consulting the specification to clarify the meaning of claim terms:

When the specification describes a single embodiment to enable the invention, this court will not limit broader claim language to that single application “unless the patentee has demonstrated a clear intention to limit the claim scope using ‘words or expressions of manifest exclusion or restriction.’” Thus this court may reach a narrower construction, limited to the embodiment(s) disclosed in the specification, when the claims themselves, the specification, or the prosecution history clearly indicate that the invention encompasses no more than that confined structure or method. See Liebel-Flarsheim, 358 F.3d at 908.

The Eastern District of Virginia’s construction of “crystalline” in claims 1-5 as “Crystal A” since the specification uses the phrase “Crystal A of the compound (I)” appears throughout the written description, and the patent offers the following definition: “any crystal of the compound (I) which shows substantially the same diffraction pattern [as in the table in col.1/claim 1] is identified as Crystal A of the compound (I).”

It would appear that Abbott sunk its own boat in dropping Crystal B:

To distinguish the invention, however, the specification refers several times to “Crystal A of the compound (I) of the present invention,” see, e.g., ’507 patent, col.2 ll.15-17, and offers no suggestion that the recited processes could produce non-Crystal A compounds, even though other types of cefdinir crystals, namely Crystal B, were known in the art. As noted earlier, the Crystal B formulation actually appears in the parent JP ’199 application. Thus, Abbott knew exactly how to describe and claim Crystal B compounds. Knowing of Crystal B, however, Abbott chose to claim only the A form in the ’507 patent.

Thus, the Federal Circuit felt that the trial court properly limited the term “crystalline” to “Crystal A.”

Product-by-Process Claims

The court then addressed the proper interpretation of product-by-process claims in determining infringement. Claims 2-5 recite a product, crystalline cefdinir, and then recite a series of steps by which this product is “obtainable.”

The Federal Circuit felt that the Supreme Court has consistently noted that process terms that define the product in a product-by-process claim serve as enforceable limitations. In BASF, the Court considered a patent relating to artificial alizarine:

If the words of the claim are to be construed to cover all artificial alizarine, whatever its ingredients, produced from anthracine or its derivatives by methods invented since Graebe and Liebermann invented the bromine process, we then have a patent for a product or composition of matter which gives no information as to how it is to be identified. Every patent for a product or composition of matter must identify it so that it can be recognized aside from the description of the process for making it, or else nothing can be held to infringe the patent which is not made by that process.

Thus, based on Supreme Court precedent and the treatment of product-by-process claims throughout the years by the PTO and other binding court decisions, this court now restates that “process terms in product-by-process claims serve as limitations in determining infringement.”

The Federal Circuit went on to ponder what it thought was the early demise of product-by-process claims:

In the modern context, however, if an inventor invents a product whose structure is either not fully known or too complex to analyze (the subject of this case – a product defined by sophisticated PXRD technology – suggests that these concerns may no longer in reality exist), this court clarifies that the inventor is absolutely free to use process steps to define this product. The patent will issue subject to the ordinary requirements of patentability. The inventor will not be denied protection. Because the inventor chose to claim the product in terms of its process, however, that definition also governs the enforcement of the bounds of the patent right. This court cannot simply ignore as verbiage the only definition supplied by the inventor.

This court’s rule regarding the proper treatment of product-by-process claims in infringement litigation carries its own simple logic. Assume a hypothetical chemical compound defined by process terms. The inventor declines to state any structures or characteristics of this compound. The inventor of this compound obtains a product-by-process claim: “Compound X, obtained by process Y.” Enforcing this claim without reference to its defining terms would mean that an alleged infringer who produces compound X by process Z is still liable for infringement. But how would the courts ascertain that the alleged infringer’s compound is really the same as the patented compound? After all, the patent holder has just informed the public and claimed the new product solely in terms of a single process.

Furthermore, what analytical tools can confirm that the alleged infringer’s compound is in fact infringing, other than a comparison of the claimed and accused infringing processes? If the basis of infringement is not the similarity of process, it can only be similarity of structure or characteristics, which the inventor has not disclosed. Why also would the courts deny others the right to freely practice process Z that may produce a better product in a better way?

In sum, it is both unnecessary and logically unsound to create a rule that the process limitations of a product-by-process claim should not be enforced in some exceptional instance when the structure of the claimed product is unknown and the product can be defined only by reference to a process by which it can be made. Such a rule would expand the protection of the patent beyond the subject matter that the inventor has “particularly point[ed] out and distinctly claim[ed]” as his invention, 35 U.S.C. § 112 ¶ 6.

For all practical purposes, product-by-process claims are now now more than “method of making” claims since the product cannot be disentangled from the very specific process disclosed for making the product.